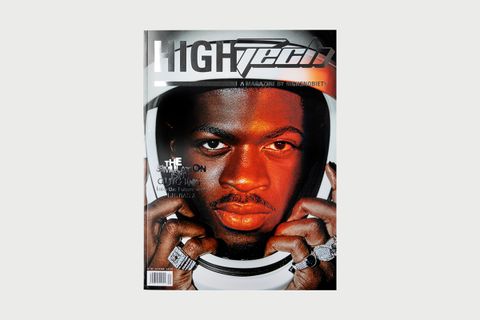

This story appears in HIGHTech, A Magazine by Highsnobiety. Our new issue, presented by Samsung, includes exclusive pages of interviews, shoots, merch, gadgets, technical gear and more. Order a copy here.

Maxwell Alexandre’s Pardo é Papel series makes direct reference to its translation, “brown is paper” — a color, not a people. In Brazil, the term “pardo” is a racial category used to classify people of mixed-African descent. It supports the colorist, anti-Black belief that the less Black a person looks, the better. With its newest chapter opening at David Zwirner Gallery in London, Alexandre’s paper odyssey continues to debunk this bias by celebrating Black pride and subverting the played-out narratives about the struggles experienced by people from his hometown.

Alexandre’s work follows his movements as a young Black man from Rocinha, the largest favela in Brazil, located in Rio de Janeiro’s southern zone. During his childhood, the evangelical gospel became a framework for life that diverted his attention from the streets, where drugs and street crime welcomed young people hoping to come up. Instead, he built a different sort of relationship with the favela through his attraction to alternative culture and skating. As a professional street and inline skater, Alexandre began to reinterpret the urban environment and the objects around him, which led to his interest in art and design.

His university studies prompted a departure from organized religion and saw him gravitating toward contemporary art and using creativity as a new tool for contact with the divine. Joining a group of artists in Rocinha, Alexandre created the Church Kingdom of Art, also known as A Noiva (“the bride”), a spiritual collective that gives a platform to young artists and an accessible art scene to the favela. He offers his work as a tithe to the Church and his community.

I’d like to read a quote from an article called “All Black Everything” by the writer Jared Sexton, which some of the works in 'Pardo é Papel' bring to mind: “Black artists making Black art move differently with and through the color black.... So even if they pivot away from figuration and toward greater abstraction, Black lives and deaths still enter the frame.” How do you feel about that in terms of your move to more figurative work in the 'Pardo é Papel' series?

Kerry James Marshall works with the color black a lot. And he does a very thorough search for specific types of black paint to talk about Blackness. That’s not exactly my area of research. There is something continuous with all of my work — there’s not exactly a separation between the abstract part and the figurative part. Even when I was making abstract paintings, I was already thinking about possible figurative works. I started out doing paintings with my rollerblades. I would put paint on the floor, and then jump onto a canvas and do markings of the wheels on canvas. But even when I was doing that, I was already thinking about possibly painting figures. It was a very fluid process.

The place for Black artists, especially in contemporary art, is often constrained by the idea that the political Black body, identity, and racial issues should always be spoken about. There’s no space for a Black artist to just talk about philosophical questions. For example, in 2017 there was this call for artists by Fortes D’Aloia & Gabriel, which is the biggest gallery here in Brazil. They opened a new space in Rio, and this was their first exhibition. The only rule was that the dimensions of the artwork fit the door of the gallery. I knew in preparation for this show that if I came with an abstract painting, being a Black painter, I’d be less likely to have a voice. So, I brought my figurative work and it gave me a platform.

The Brazilian philosopher Djamila Taís Ribeiro has argued that the person who has experience needs to be the first to speak about it. It’s difficult to find someone from a favela with experience plus knowledge of the codes and rituals of the art world. It’s something that was lacking for a long time, but now, more people are embracing it. The Pardo é Papel series is about empowerment and self-esteem.

Speaking of Kerry James Marshall, your piece 'Peço bênção pra sair e pra chegar' [“I ask for blessings to go out and to come back”] references his work, right?

Kerry James Marshall is someone who has achieved the kind of acknowledgement, research knowledge, and financial achievement that I aspire to as a Black artist. This piece is an ode to him as someone I respect and look up to, and who’s been in that space before me. The title is from a verse referencing the deity Eshu from the Afro-Brazilian Umbanda and Candomblé religion. Some of the Eshu in Umbanda are mischievous and may have a look similar to the face in the background of the painting, one of Kerry’s most famous pieces. He’s in this separate room and sort of represents this ancestor.

Many of the paintings in the series celebrate moments of subversion — especially with identities that are surveilled and policed. You’re showing many levels and variations to the identities of Black people in Rocinha and exploring concepts like the Garden of Eden full of Black bodies, as well as themes from modern-day technology. How are you choosing the voices you highlight?

So, there are a couple of layers to this. First, the canvas was strategic. Having a painting on the wall is the most esteemed mode of art. Then there’s the construction of the ideas and stories inside the canvas. I’m taking brands and symbols of poverty, and putting them into a different perspective — like someone in an empowering pose with blonde hair or someone with a lot of money tanning in a plastic pool. In the favelas, people put these pools on top of their houses. For the rich, they’re a symbol of poverty. But inside the favelas, they’re a status symbol. It’s a way to show that our status is real.

The relationships I establish between objects and people are already a subversion, simply by dealing with the universe of art and being a young, Black painter. Pardo é Papel is ostentatious, so it’s showing empowerment and Black bodies inhabiting places that are not meant for us. It’s iPhones and money, everything that would bring pride or status to a figure. The painting is altering the circumstances. That painting with the garden, Me dê a maçã or “Give Me the Apple,” comes from a verse from the rapper BK.

There are quite a few rap and poetic references in your paintings, right?

Sometimes I use the verses literally and sometimes I alter them. In this situation, the verse is, “Eve gave me the apple, but it turned out to be her iPhone number.” So, it’s the idea that the apple from the garden is also the number from the iPhone of the girl I met. It starts from this kind of ideation from a verse, and then I construct a whole universe around the sentence.

You released an album in April called 'anjo Maxwell' [“angel Maxwell”]. Is there an overall relationship with music as it attends to your visual art?

Music used to be in the background in my life. I didn’t understand anything about music, but my relationship with it changed in 2017 when I started selecting rap verses from Baco Exu do Blues, BK, and Djonga, which inspired me to construct my series Pardo é Papel. I started painting about self-esteem and empowerment in the Black community, and these poets were talking about the same things I was representing in my work.

I had the chance to get closer to them backstage at their concerts and in the studio. Something woke up in me with the writing, beat selection, and even recordings. I had already done an album with A Noiva entitled Coral ("Choir"). It was our first art studio album. The project was all recorded in just one day in my studio here in Rocinha with other members of the Church.

I saved the release date for April 1 to symbolize venturing into things I’m not entirely sure of. On April 1, 2019, I got married within A Noiva. I’d never had a girlfriend before. I didn’t make our relationship status official before we decided to do it — on April Fools’ Day. From this act, the date was defined, to me, as the day that I move myself into the unknown.

anjo Maxwell is my fourth tithe to A Noiva. The most intense part of this project happened within two weeks, and even with all the challenges with the pandemic, I was completely focused on the timing. The work is an album to build the faith of other artists. I like this connotation because it’s exact when I think that the work was marked by the beginning of quarantine, when social isolation brought us anxiety and an uncertain future.

With A Noiva, you and other artists have created a unique spiritual and ritual practice, which isn’t really rooted in organized religion, but more connecting to your own sense of divinity through art. Are you also capturing that spirit through storytelling in your paintings?

Being from Rocinha, having a kind of forced evangelical education was a sort of safe space, or protection. You have drug trafficking going on and all sorts of crime. Of course, being raised by a mother who was evangelical kept me from engaging with that, because the gospel condemns any kind of relationship with that. It’s a strong moral compass. It’s hard for young kids from here because you get in touch with things early. University challenged my relationship with religion. My mom used to say the more knowledge you acquire, the further away you are from God. Having this education was indeed the first time I started deconstructing the religious side of my life. I got in touch with other gods, mythologies, and dogmas that come with academic knowledge. Then I got in touch with contemporary arts in a class taught by the painter Eduardo Berliner. That’s around when art became my religion and I began to see myself as an artist.

Do you see your art as another way to help people in your community connect to this concept of the divine?

There is this idea that by getting in touch with a work of art, you can have this singular moment or sublime sensation. Of course, contemporary art has always been elitist and a bit exclusive, even among the super rich. If I take one of my friends from Rocinha to a museum to see a Barnett Newman, he’s probably going to laugh in my face at seeing the blue background with just a white line in the middle. No one here has time to reflect endlessly about a subject like art. Life is more urgent than that.

The idea is not to get these people to feel the sublime sensation. They already do that in other parts of their lives. It’s making them realize how they can hack the art world to get financial and social gain. It’s more like a cynical or very objective way of looking at art. By seeing me doing well, and getting money out of it, it makes them realize that you can be whatever. You can be a soccer player. You can be a drug dealer. You can be a rapper, or you can be a contemporary artist as a way out of this ever-maintaining system.

It’s an interesting way to subvert the conversation.

Yeah. We’d do shows and bring works of art to the street to bring the conversation to people who were just passing by. It’s an idea of putting that into tension. Bringing these ideas to the table.

Visit Maxwell Alexandre's 'Pardo é Papel' at the David Zwirner Gallery in London.