.bg-image.parallax__element.px-full-width-media__background { position: absolute; transform: translate3d(0, 0, 0) !important; height: 100% !important; } .hs__custom-header a { color: #fff; text-decoration: underline; } .hs__custom-header a:hover { color: #fff; text-decoration: underline; opacity: 0.8; } .hs__custom-header { position: relative; color: #fff; padding: 280px 0; } .hs__fading-background { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; } .hs__custom-heading { text-align: center; margin-bottom: 150px; } .hs__custom-heading .headline-element:first-child span { text-transform: uppercase; } .hs__custom-heading .headline-element span { font-size: 3.5294117647rem; } @media (max-width: 39.99em) and (min-width: 23.4375em) { .hs__custom-heading .headline-element span { font-size: 1.4117647059rem; } .hs__custom-heading { margin-bottom: 50px; } .hs__custom-header { padding: 80px 0; } } This story appears in Issue 16 of Highsnobiety Magazine.

Off the M train at the border of Brooklyn’s Bushwick and Bed-Stuy neighborhoods,the scent of artisanal coffee that signals a‘hood on the cusp of gentrification, slithers up a flight of stairs, seeps through a crack-opened door, and meets the sound waves of jazz crooning to the beat of an active paintbrush. Miles Davis’s Kind of Blue is on repeat, and the tunes of “Blue in Green” fill the sunlit atelier of 31-year-old artist Reginald Sylvester II.

On one side of the studio, a massive canvas hangs off a 10-foot-tall wall, hovering over a neatly arranged lineup of iconic footwear models—amidst them are Air Jordans, Converse 1970s Chucks, Vans, Doc Martens, Nike Air Force 1s, and a couple other prototypes from sneaker history’s masters. On the other side of the room, a stacked collection of books, revealing titles of art history’s Modern masters:

Tadao Ando Cy Twombly Picasso’s World Willem De Kooning Sterling Ruby: Chron Big Shots: Phillip Leeds Lee Krasner: A Biography The History of Modern Art Interviews with Francis Bacon Happy Birthday to You by Dr. Seuss Irving Penn: Centennial Exhibition Catalogue The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language and a sketchbook, opened to a page marked with the word SOLITUDE

Dressed in Levi’s, a vintage army cap, and a pair of powder-blue Japanese house slippers, the artist stands between the wall of kicks and the shelf of books, in a metaphoric meeting point of the ages; in between street culture’s low-key cool and history’s high-brow heritage. The intersection of high-tops and high-art, both conceptually as well as literally, is one that continues to run across contemporary culture—most notably, with today’s unending slew of collaborations that attempt to genetically-modify everyday objects into limited edition works of art. Yet in our perennial, millennial quest to find (and post) something legitimately cool and fresh in our material culture, we are obliged to turn our attention away from the latest drops and brands, and go back to art and the artist. For the very je ne sais-quality that culture seeks to perform with collaborations—a fusion of opposing forces that will lead to new artistic results—is precisely what Sylvester accomplishes alone through painting.

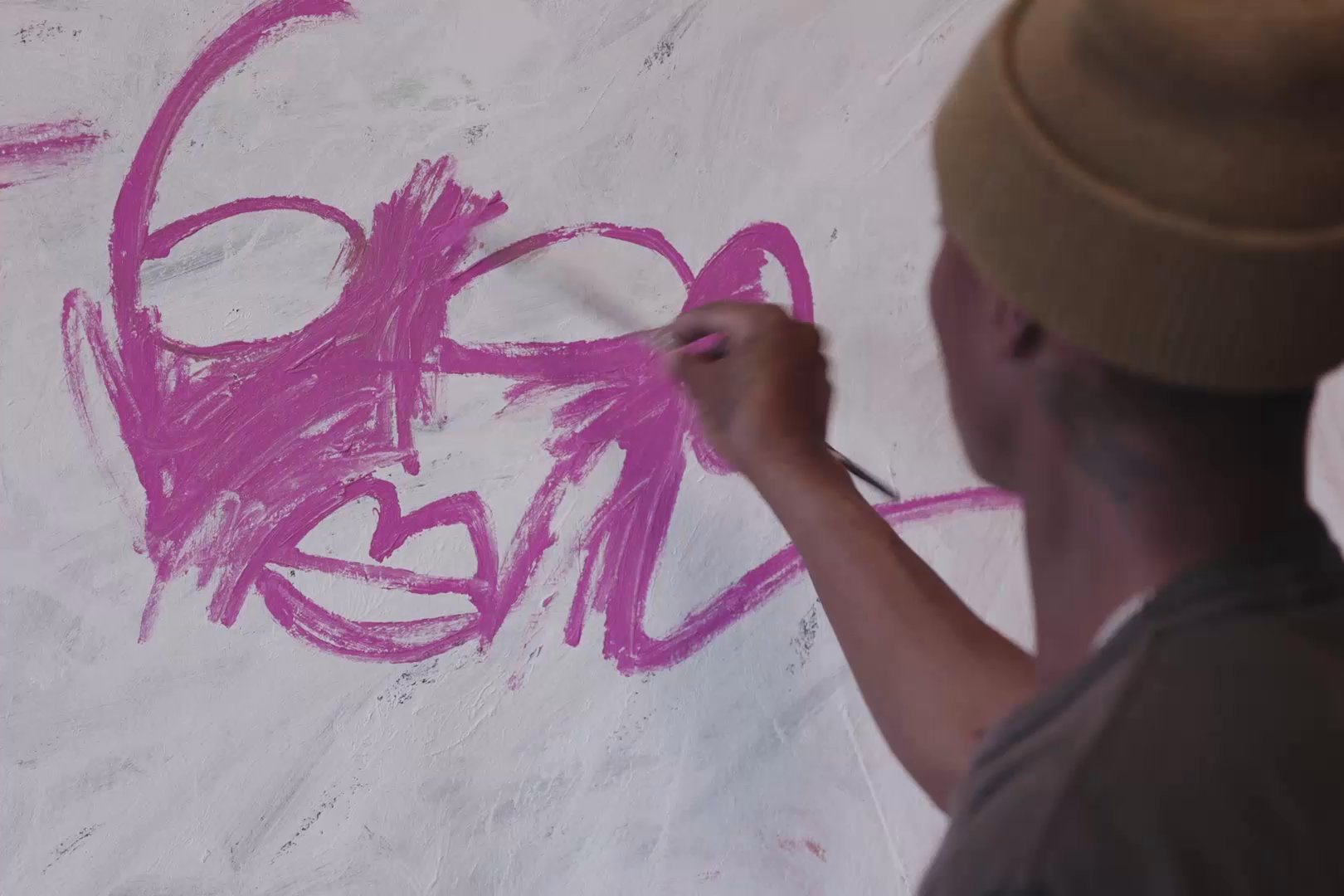

Approaching the work of art in this vein, Sylvester works like a mad scientist without goggles, seeking to strike an ideal balance between various pairs of contrasting bodies: stylistically, between figuration and abstraction; formalistically between sharp lines and organic, sinuous movements; psychologically, between painting for himself and making for a public, and anachronistically; between history and the future of art.

Turning his back to the bookshelf, Sylvester looks towards the massive, unstretched canvas, and makes eyes with the lone figure painted on top of it: a compendium of green and black markings offer the painterly suggestion of a shoulder that supports, if only by a few scribbles, a skeletal face with a wide, grid-like grin made from paint as thick as cream. Confrontational like a De Kooning Woman, the figure stares back at the artist through two sketched orbs and a bright case of acrylic red-eye.

In a moment, he breaks the stare-off, picks up a tub of orange acrylic paint and dips a thick-tipped brush inside. First touching the figure’s face, he then starts to make wide, windshield-wiping gestures over it, moving back and forth in a sort of solo ceremonial flick of the wrist until he has covered up and drowned the entire body under a sea of orange.

Wide-eyed guests in the studio don’t say anything, but their dropped jaws suggest the collective thought that Reginald just ruined what was the making of a masterpiece. But the artist is chill as ever, and dipping his dripping brush-head back into the tub, looks back contentedly at the canvas, blinks, and takes the last sip of his almond milk flat-white.

“It wasn’t strong enough,” he comments. This instinctive gesture, expressed through layers of ferocious placements of pure unmixed colors, have turned into a sort of CTRL Z methodology that defines his practice. “I put stuff down, I take away, I build up again, I take away. It’s not about making a picture, it’s about finding it.”

Unbeknownst to the viewer, any one of his paintings might be the last layer up of what was once one, two, or five more painted characters that now lay dormant as part of an acrylic millefeuille, rendering each canvas like an archeological tell preserving the bones of erased peoples.

“My paintings are never planned,” he explains of the process. “They come with momentum. They come naturally.”

The artist’s career, like his work, mimics the same fierce momentum, and it is still picking up speed. With a mind that works as fast as his hand, Sylvester departed from a career in graphic design and the streetwear scene, to bolt up, and bolt down, the art world’s unstable ladder. The response to his efforts is nothing less than remarkable. In just a three-year period, Sylvester has already exhibited at Art Basel, had a solo show at Pace Prints in New York, took up wall space at Milan’s Fondazione Stelline (who then acquired his art for their permanent collection), and recently stopped traffic of the suit-and-tied Park Avenue passersby with a huge solo show visible through the sparkling glass walls of the Lever House, ran by art mogul Aby Rosen, who is also one of Sylvester’s collectors.

It is perhaps of no surprise that an art tycoon like Rosen would be drawn to the young artist. Rosen’s own impressive collection, rumored to have over 800 works, includes those by art history’s bigshots found on Sylvester’s bookshelf—Jean-Michel Basquiat, Alexander Calder, Andy Warhol, and Richard Prince, to name a few. For any fan of modern art then, there is something oddly comforting about the painterly agita found in Sylvester’s work. They present a sort of contemporary dreamscape or, an anachronistic collaboration with the 20th century’s creative zeitgeist for abstraction with figuration. For if we dared to imagine what a millennial maker would do if Picasso’s African masks would fall off his 1907 Demoiselles, land beside a sinister George Condo, get picked up by a De Kooning Woman under a sky of Twombly squiggles, then we might find ourselves looking at something like a Reginald Sylvester II.

Yet while looking back to the past, both art history’s and even his own, the artist moves forward to create a provocative art of today. His aestheticization of issues concerning race, sexuality, or religion grace us like a contemporary oracle, met with an unprecedented level of self-awareness that most young creatives today lack. Sylvester’s existence as an artist relative to the age of technology he lives in also informs his art further. A repetitive grid in a drawing may reference our digital culture and its endless possibility, while simultaneously signifying the artist’s entrapment within it. He admits that he tried to get rid of Instagram, adding “I’d rather just be a hashtag”—he was accordingly advised against the departure.

To create anything, he explains: “My energy is transferred onto the surface, while the imagery is streamed from my subconscious, which I believe is the soul.” For Sylvester, painting ensues as a series of oppositional collaborations, layered with introspection thicker than paint, and meaning beyond that which meets the eye.

Accordingly then, even the creation of a zine transgresses being just a collection of printed images, but rather a chance for the artist to create what he sees as a “solid object,” through which to express himself and experiment with composition. Sylvester is making his own visual language. Colors are consonants, doodles becomes verbs, shapes sound like vowels, and lone letters and numbers act as footnotes. The result strikes nothing less than a powerful equilibrium between high and low, old and new, the dope and the didactic.

“You’re making by living, you’re not making by making. And that’s best shit ever,” he says. During a recent studio visit, the artist discussed these forces around him, and his own collaborative relationship with the past, the present, and the future of creative practice.

---

How do you define “artist”?

An artist is a professional risk taker. It’s the job of an artist, or any creative—to take risks that the average person isn’t supposed to.

So if we wanted to apply to be a “professional risk taker,” what skills would be needed on an artist’s “resume”?

List: - Being unafraid - Ability to work without pay or other’s gratification - Extreme mobility - Ability to work in uncomfortable situations and environments - Willing to try things that have and have not been done before

Let’s talk about that last point—trying things that have been done before. Your work is often compared to some of history’s greats, but it is more than a healthy Basquiat, just like Sterling Ruby is making more than just “gangsta Rothkos.”

I don’t think you can expect to create the future without having an understanding of what it took to create the past. In any industry or area of creativity, working with any medium, the investigation of what happened before you is a critical point to understanding how to move forward. People don’t always understand that. My art is not just derivative or a carbon copy. In actuality, what I’ve been able to do is to evolve in front of people. This is also what it means to be unafraid, and that is what makes me an artist of today. I have shown everyone this evolution on all platforms—through social media or exhibitions—I have shown the research for you to see. This is necessary to create art of the future.

Are people educated enough about Basquiat to understand how your work relates to it, but also how it differs?

I don’t think this new generation of individuals is educated on Jean-Michel nor other artists, nor even know why they are so pivotal to art history in its entirety. His image got so popular not only because the work was strong and new but because he was actually invested in the culture and what was going on at that time he made it. The moguls then were so aware of his importance. That doesn’t necessarily exist nowadays as it did. I get compared to Jean-Michel a lot, sure. He’s the immediate influence people like to call out. I feel that is partly due to the reason that we are both males of color and painting in the vein of abstraction and figuration. For me, it’s about how automatic he was. Jean-Michel wasn’t classically trained, nor am I. Everything I have done has been my own journey and figuring it out for myself. Getting the comparison pushes me. I think an artist’s job is not only to discover things about themselves but at the same exact time they are supposed to speak to art history and bring it to a new space. I am working to do something different in my own search for truth. These are only starting points for me.

Any reason you’re on a first name basis with Basquiat?

Everyone calls him Basquiat, but he was also a human being. Jean-Michel makes us remember he was once a person and not just a brand. A lot of artists become brands after they die.

A lot of artists today become brands while they are living.

Yes, for those who produce their work instead of create it. In a lot of cases, big artists turn their work into products through licensing or collaborations, or simply by having other artists make it for them. People feel they can stand behind a brand for certain aspects of what they do, be it an aesthetic or quality they admire. So an artist should strive to be his or her own brand, but by making things, not having people do it for them.

You made a conscious shift from using the name Slvstr©, to use your birth-given name. One seems more like a brand, and the other like an artist.

Exactly. As a designer working for corporations or on freelance projects I used Slvstr©. I wanted to be respected for my creativity—but as a graphic designer I always had clients telling me what to do and I hated that. I gave it up and I made the change, primarily because I wanted to be free from those constrictions and to be acknowledged for my own artistic voice. I was always confined in a sense, whereas with painting, I am not.

How do you balance the need to see what other artists are doing while also remaining in solitude?

It’s exciting to go out and see other people’s work to get inspired, to know what is going on around me, and to know what your contemporaries are doing. But for me, spending time in the studio and pushing my own limits and boundaries is just as important and if not more important than going outside. I spend a lot of time alone—sometimes it’s not about making a painting, but it’s about thinking and understanding what is happening in my own life and the world around me.

So are you painting for yourself, or for a viewer?

The only time it’s for me is in the process of making—to take my relation with figuration and abstractions to the rarest place, and push myself to make the strongest painting that I possibly can. I don’t consider the viewer while making the painting, but only after it is displayed. Once it leaves the studio, it isn’t about me.

How do you define when your painting is “strong”?

It’s not strong if it’s not strong enough for me to not paint over it.

The covering up of images defines more than your practice it seems.

If I don’t feel that it’s strong enough I cover it. The paintings that existed prior were cool but even after making something, I realize certain areas could be stronger. I can get bored easily too, so if I did something similar to what I’ve made before I’ll change it.

So even if it is not a self-portrait, you’re always in the work?

Yes. The process becomes about making what’s most recognizable to me, paintings that scream Reginald. It’s about finding what feels right, allowing the opportunity to discover new things while asking myself, can I push this further?

You have a profound mastery of color.

I actually learned how to use color by making realist portraits of rappers with color pencils in high school. As a graphic designer I worked with colors and their transparencies using the swatch palette on Illustrator. I don’t mix colors before applying them when painting, so the process is very much like the digital one—same relationship, just composed differently.

That’s a very contemporary approach to painting. How else does today’s digital world affect your art?

I use Instagram as a tool more than anything. It’s a place where people can interact with my work and what I am doing. Taking photos of my work with my iPhone and critiquing them is also a part of my editing process. It sounds weird, but there are things that I see in the work through the phone that I don’t see in person.

Mark Rothko is a great example of an artist who aimed for his paintings to elicit overwhelming responses in his viewer. But he even returned a check after accepting a massive commission for the Seagram Building (now owned by Rosen) when he realized the paintings would not be able to affect the viewers to the degree that he wished. Today, people are missing out on experiencing certain visceral reactions the artist intends—especially because they are looking at art through a phone.

It’s a battle in the day and age we live in. Through media and Instagram we are being fed a lot of things and told what to like—we have an “explore page,” that thinks they know us, but those images are not making us feel anything. Looking at a painting is an experience. That experience is not even a quarter lived when viewing through a phone.

Is there any way to recuperate this loss? In other words, if the viewer loses something from not having an in-person experience, can they ironically gain something else from the digital one?

The only way is for people to come and have the experience in person. We need more of that anyway. I do believe there is something to gain from the digital one and that’s informing the people that something is going on—to move them in a way where they want to get from behind their phones and take part in the moment.

The “Brand × Art” collaboration is a pop culture phenomenon. At times these liaisons can extend an artist’s repertoire as well as the brand’s narrative. But often we find they can undermine an artist’s work and make brands seem like creative posers. What is your take?

Collaborations can give artists a new platform and audience, and it can give viewers a new surface to experience an artist’s work. Seeing a painting or sculpture in a physical space like a museum is a type of engagement that can also teach us why the artist made it in the first place. That is missing I feel in [Brand × Art] collaborations—the educational aspect, the reasoning, the story. A [Brand × Art] collaboration being bought by an audience who understands the significance of the brand yet not the significance of artist I feel is a disconnect. This allows the creation to become less important I feel and more about how much it resells for.

What’s your dream collaboration?

COMME des GARÇONS.

You were an apparel designer for the youth-oriented streetwear line Rare Panther, so it’s notable you choose an avant-garde brand like COMME today—a departure from your earlier interests in streetwear. Is the choice of fashion house parallel to your evolution as an artist?

I’ve always loved and admired COMME. They’ve engaged in streetwear at certain points. I feel that there is a parallel in my work currently and how COMME des GARÇONS composes their garments. They find beautiful ways to use color and I’ve always enjoyed how they strike a balance between fun yet serious and sophisticated compositions. They always play with texture which I love too. My own work has something fun, vibrant, and textural, but it also has such serious undertones. I think Rei Kawakubo has been able to create that balance so well. What’s great is that their retail store is in the heart of Chelsea, beside all the art galleries, rather than in SoHo.

How did your relationship with fashion and streetwear begin?

Going to the Academy of Art University in San Francisco, my dorm was next door to the HUF stores on Sutter Street. I was being introduced to the brands that thrived in those spaces which increased my interest in them, and especially how they connected back with sneaker culture. I was also drawn to Japanese streetwear brands for their attention to detail. My favorite to a name few: fragment, Uniform Experiment, Vanquish, NEIGHBORHOOD, WTAPS, and BAPE. Today, I’m less into streetwear labels but more so into fashion brands and houses. Besides COMME des GARÇONS, I’ve always loved what Junya Watanabe and visvim do.

How do you balance representational works with abstractions?

Through building and taking away over and over again. It’s more of a feeling than a calculated process. To master this balance for self is a lifelong journey.

How do you use painting as a tool for personal discovery?

Through the process of making I think about things going on in my life or the world at the moment, and I confront these issues. I get lost in my thoughts and feelings, and then the pictures come out of that. That is why solitude is so important—the best works come from when I’m conflicted or in momentum. Painting is me learning about myself.

---

If creating art is Sylvester’s process of self-exploration, then answering questions about that very practice while painting in his studio, has lead to the creation of a surprising new masterpiece. And we are looking at it. The massive canvas of the lone figure we feared drowned in orange, now shines brightly instead with two men in swirls of pure magentas and greens. One, painted on his profile, looks away beside the number 30. The other, looks forward, smiling greenly beside a 31.

The strength and battle between the figures is palpable—like a scene of brothers, perhaps Cain and Abel, or maybe Isaac and Esau fighting in the womb—or perhaps they are like two muscular male nudes caught in a sporting game on a Greek urn. Sylvester stands in front of them, and the figures start to transcend biblical or historical references, or even styles evocative of some great master. Rather, wavering between abstraction and representation, they ensue as a double portrait of the artist himself, who speaking of his work, paints that very process, looking back if only to move forward. He smiles back at the figure, knowing this time he has created a strong work to be released for the world. Or, himself.

Highsnobiety Magazine Issue 16 is available now from our online store, as well as at fine retailers worldwide.