Highsnobiety Q1 is the latest in a series of quarterly insight weeks dedicated to the business behind youth culture and what makes our market tick. Head over to our Insights hub to see the full series.

In 1999, The New Yorker released one of its most iconic articles ever published. In “Don’t Eat Before Reading This,” the late chef Anthony Bourdain spilled trade secrets of the restaurant industry. In doing so he poetically painted a picture of what it’s really like being a chef, to those who rarely get a glimpse behind the scenes. In this FRONTPAGE feature, veteran fashion writer and critic Eugene Rabkin takes a similar approach. As our industry has become increasingly global, saturated, and polarized, those observing it think they fully understand what the industry has become, they rarely do.

Fashion is like high school but with $1.5 trillion dollars at stake. There are the popular kids, the jocks, the cheerleaders, the nerds, the sheepish outsiders. The entire industry that employs designers, creative directors, models, celebrities, public relation firms, editors, influencers, show producers, photographers, stylists, makeup artists and hair stylists, and the armies of assistants and interns that support them, runs on insecurity.

Karl Lagerfeld — fashion’s late prom king — knew this well and cut people down deftly and ruthlessly. One of the few people he would not cross is Anna Wintour, the editor of American Vogue and fashion’s prom queen. But he did unceremoniously discard others he deemed no longer relevant.

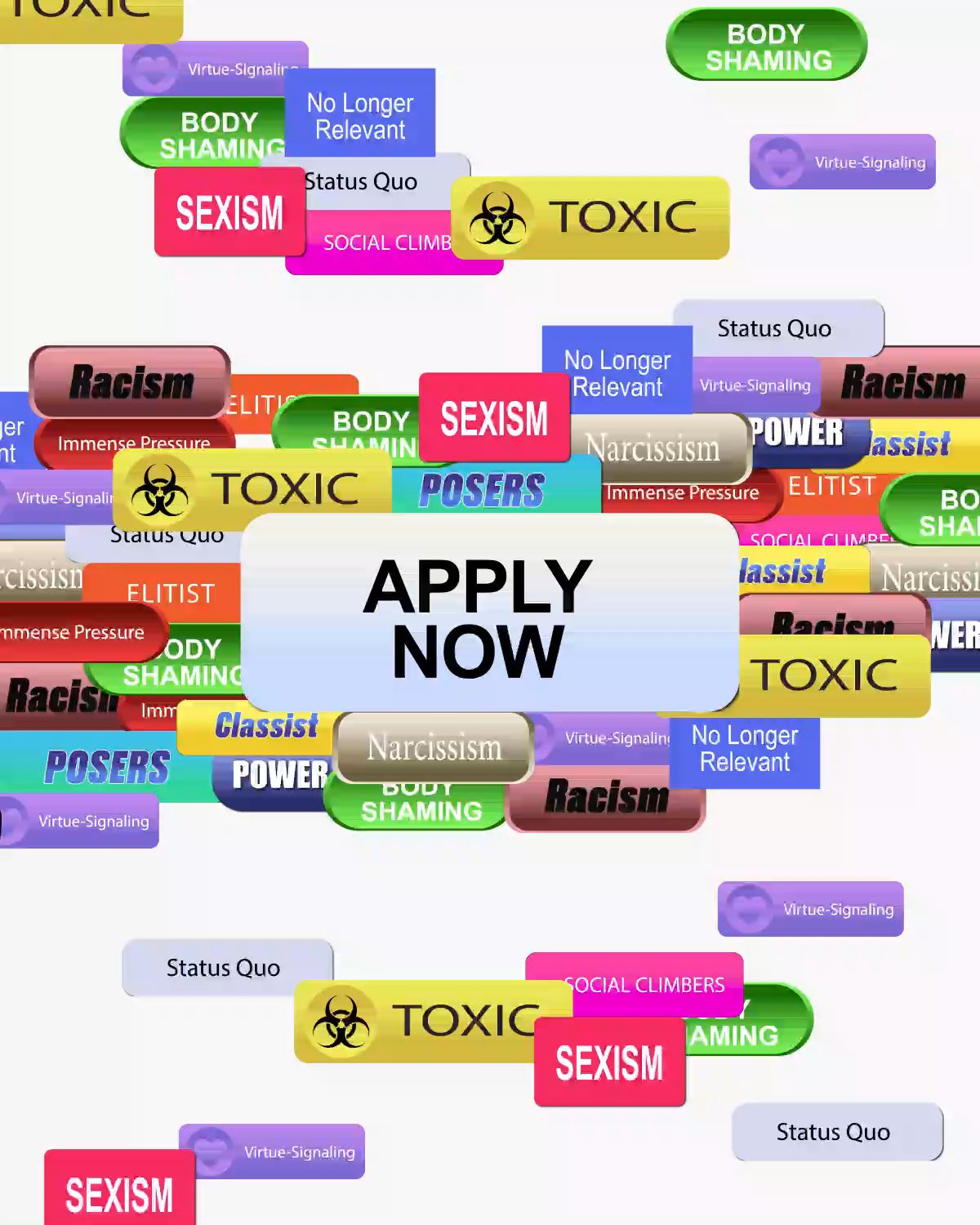

Dealing with unhealthy doses of narcissism, with big and fragile egos, is part of this work. Fashion is full of shameless opportunists, posers, and social climbers, people who indiscriminately shove their business cards into everyone’s hands, their eyes shining with greed for power and access, constantly working the room, looking over your shoulder to see if there is someone more important they should be talking to instead. Fashion comes with various forms of abuse — mostly emotional, and, as we are now witnessing, sexual — from people desperate to hold on to whatever modicum of power they possess. In fashion, rampant drug use, long working hours, immense pressure, and equally immense privilege make for a toxic mix of general nastiness, the contents of which — racism, sexism, body shaming, all kinds of abuses of power — are now being dredged up after years of being swept under the rug.

Fashion keeps its grip on its hierarchy as tightly as an aristocracy that knows its hegemony is temporary. The industry’s economic and cultural impact is vast, but behind its forward-looking veneer is an essentially conservative industry, slow to change, often paying lip service while doing its best to maintain the status quo. Fashion has always been the great illusion maker, and it has lately turned its knack for smoke and mirrors into the great virtue-signaling machine. It bullhorns sustainability, yet its core business is selling as much clothes to as many people possible. It ostensibly champions democratization while trading on exclusivity. It sells aspirational product, while carefully hiding the fact that the truly rich often don’t really care about fashion. It nods enthusiastically to demands for inclusivity with token gestures.

Fashion’s gatekeepers keep the gates tightly shut, promulgating the you-can’t-sit-with-us mindset. A sizable contingent of people who want to be in fashion have realized long ago that they cannot depend on the existing power structures of glossy magazines, fashion councils, and conglomerates, and have formed their own networks, at times with great success. With the democratization of access through the rise of new media and different modes of fashion like streetwear, things are slowly changing, but it remains to be seen whether we are not simply exchanging one power structure for another — it’s a historical truism that people in power will inevitably abuse it.

Fashion is like high school but with $1.5 trillion dollars at stake. There are the popular kids, the jocks, the cheerleaders, the nerds, the sheepish outsiders.

In my line of work, abuse of power comes mostly from public relations agents, and I’ve experienced it more than once. Usually, the damage is done with a smile and a stab in the back, but sometimes straight to your face. The first time was at a Valentino show at Pitti Uomo trade fair in Florence, where the PR person who kept the answer to my request for a ticket vague for several days pretty much slammed the door in my face. “Well, I’m not getting in either!” — a lie — he snarled, after I pointed out that I cannot write a proper report on the fair without having seen its main event. Throughout our codependent relationship, which we rekindled twice a year during the fair, he was nice to me for the first ten minutes the first time we met, until he figured out my pecking order on the journalistic totem, which wasn’t very high, since I did not possess a Condé Nast business card.

PRs are the bane of every journalist who is not a member of the upper echelon of a major magazine. Though PR agents come in all shades of personality — from the kindest to the meanest — their superpower is saying “No,” and many of them have no qualms about using it early and often, sometimes to the detriment of their clients.

I have always admired George Orwell, who famously refused to meet the authors whose books he reviewed, fearing that acquaintance would taint his sense of objectivity. In fashion journalism such a stance is impossible, unless you plan on not writing at all. Fashion is an insular industry, and to gain access to a designer for an interview you will most likely need to go through PR. This is when power games begin and journalists buckle under pressure, engaging in most egregious self-censorship.

Over the years, the PR industry has gotten more insidious, often asking journalists to show them an article before its publication, to which my answer is a poignant “No” (though I will go back to them for fact-checking), or demanding that stylists only shoot full looks, turning editorials into de-facto ads. Increasingly they also ask for email interviews. That’s a double “No” in my book, since there is no way of knowing who actually writes the answers, and more often than not you get canned responses designed to say nothing in so many words. I once turned down an interview with Hedi Slimane for a major international publication after they told me that an interview would be via email. The fact that they agreed to it was dispiriting enough.

Often PRs are knowledgeable, but sometimes they are clueless to the point of absurdity. Several months after I annihilated a show of a famous designer on the pages of this publication, I was invited to his house to do another article on him for a prominent international menswear magazine. “Do they not Google the journalists they invite?” I asked my editor. He shrugged his shoulders. I was sure that they’d retract the invitation at the last minute, but they didn’t. While the photographer and I were waiting for the designer’s girlfriend at his house, the former asked, “How did they let you in?” Clearly, he googled me.

It bullhorns sustainability, yet its core business is selling as many clothes to as many people as possible. It ostensibly champions democratization while trading on exclusivity. It nods enthusiastically to demands for inclusivity with token gestures.

Fashion is elitist. When its elitism comes via meritocracy I am all for it, but when it does not, it mangles people. Fashion is also woefully classist. It’s not just the shiny facade of glamour that fills the ranks of the industry with rich bubbleheads who equate their love of shopping to a love of fashion, it’s the fact that the industry is designed to facilitate them and keep the poor out.

Only the slim minority of the people who work in fashion make a good living. The rest are either scraping by or rely on their parents for help. Many interns at Vanity Fair were children of celebrities who in the past could not get in without their parents having Graydon Carter, its fancyman editor, on speed dial. According to an article in Fashionista in 2019 the average salary of an assistant market editor was $25,000, with many other lower echelon salaries hovering around the $40,000 mark for decades, despite inflation. That is not a livable wage in New York City, or London, or Paris.

For those who cannot draw on unlimited credit at Bank Dad, there is the secondary market on which junior editors frequently sell all the stuff they get for free. Because it used to be seen as unsavory, this practice was done with utmost discretion until fairly recently, when the norms of separating the media and commerce — what used to be called church and state — were erased. Now, what used to be thought of as a bribe has become a legitimate source of secondary income. Of course gifting is just another avenue used by brands to gain favorable coverage (which today can simply mean an Instagram story), the carrot that complements the stick of denying access and pulling advertising. And as major brands have become richer and the media poorer, the brands now hold a lot of cards in their hands.

Fashion criticism is nearly dead. I can count on one hand the number of fashion journalists who still dare write a critical review about a collection they did not like. This is why the best fashion coverage is often found not in the glossy fashion press but in major newspapers like the New York Times and Le Monde and in general interest magazines like the New Yorker. What people in fashion, blinded by narcissism, forget is that criticism exists in its service. When I am critical, nine times out of ten it means that I want a designer — unless he is Philipp Plein — to do better (if I don’t like a brand I won’t go to their show in the first place). It’s because I want fashion to be better.

But impoverishment of fashion criticism goes hand in hand with impoverishment of fashion itself. Over the past two decades we have witnessed the biggest brands tightening their chokehold on the industry, as well as a deterioration of standards across the board, from quality of ideas to quality of garments. Gone are the days of the kind of anarchic excitement that surrounded the Antwerp Six and the second Belgian wave, the pointedly anti-luxe esthetic of Comme des Garcons and Yohji Yamamoto, the awe-inspiring artistry and showmanship of Alexander McQueen and John Galliano, and the cerebral experiments of Hussein Chalayan and Martin Margiela. The discerning audience that appreciated this kind of work has largely disappeared, and I am not quite sure why.

And yes, I have met the most wonderful people through my work, too. People who are kind, gracious, passionate, and incredibly creative, who love fashion despite all of its drawbacks.

And yet, and yet… I wouldn’t trade this job for anything. I came to New York from a country where nothing ever grows, to a Brooklyn neighborhood where nothing ever grows (or as my barber puts it, “No one is here by choice.”). Culture, and fashion as part of culture, has always been my lifeline. Instinctively, I came to understand early on in my teenage years that what you wore on the outside signaled how you felt on the inside. When I discovered that there existed fashion that was having a conversation with the music that I loved, I tumbled into that rabbit hole with glee. Fashion was my armor against the world I did not particularly admire. I felt closer to the strangers who made these clothes, the same way I felt closer to the strangers who wrote my favorite books and produced my favorite records than to my family and my peers. So when years later I got an opportunity to write about these creators I admired from afar, I did not think twice.

When fashion is at its best, it’s pure magic. The beauty, the theater, the craft, the meaning designers create with cloth and scissors and their co-conspirators with cameras and makeup; the lasting images embedded in your head for decades, the way fashion interacts with art and music, all of it creates lasting and deeply satisfying impressions. The sheer excitement of being at a great fashion show is hard to beat.

The first show I attended as a journalist was the last Number (N)ine outing in Paris in January of 2009. In a sparse space on Quai Malaquais, Takahiro Miyashita presented his final stroke of genius before quitting the brand. Besides the intricate, almost surreal clothes I remember the unusual circular seating arrangement that split the audience into chunks, and the veiled models slowly swirling to the cri de coeur soundtrack by Beth Gibbons, the singer of Portishead. In my third-row seat I felt immensely privileged to be there, like a fan who snagged the last ticket to a sold-out concert by his favorite band.

I was fortunate that my first show was a fashion moment, an event that years later gets people to say "remember that?" I have witnessed many since, whether it's Rick Owens building monumental scaffolding in the courtyard of Palais de Tokyo, or Jun Takahashi and Takahiro Miyashita’s Order / Disorder double-header at Pitti Uomo in Florence that left the audience speechless. I cherish the times the PR company that knows me all too well sat me right behind Patti Smith at Ann Demeulemeester and one seat away from Thom Yorke at Undercover.

And yes, I have met the most wonderful people through my work, too. People who are kind, gracious, passionate, and incredibly creative, who love fashion despite all of its drawbacks. What I love about these people is that they are misfits, like me. They are the former artistic kids who were bullied in high school, the ones who refused to “grow up.” They are the cultural minorities who view aesthetic expression as a form of escape — the goths, the punks, the emos, the all-round creative class. They are the queers who have been shoved by this society into work that was not deemed serious, until it became serious and the suits moved in, as they always do when they smell money. They are the aspirational class — the immigrants, the expats, the minorities, the restless souls with the kind of passion that often comes from desperation and the desire to make something out of nothing.

Anthony Bourdain once said that no matter how successful he became he always felt like he’s driving a stolen Ferrari, constantly checking the rearview mirror for the cops. This is how I feel, even after more than twelve years writing about fashion. Two years ago a prominent critic, exhausted by the gruelling fashion schedule, of everything being suffocatingly mediated and managed, by having to attend shows of brands where positive coverage was bought and not earned, asked me if I ever considered changing my career. I have not, and I can’t wait to get back into my cramped economy class seat when Covid ends, to be jet lagged and sleep deprived, to hurriedly run around Paris in the undying hope of catching another fashion moment.